The first new national blood pressure guidelines in over ten years are out, and I think it fair to say that they say as much about how medicine is to be practiced in the future as they do about the treatment of blood pressure. First about the recommendations themselves:

The first new national blood pressure guidelines in over ten years are out, and I think it fair to say that they say as much about how medicine is to be practiced in the future as they do about the treatment of blood pressure. First about the recommendations themselves:

- For most people the goal remains to get the blood pressure below 140/90

- However, for those over the age of 60 the goal shifts to 150/90

- For those with diabetes the goal blood pressure is no longer 130/90 but shifts to that of the general population, ie. 140/90 and 150/90 for those over 60. Ditto for those with chronic kidney disease

- For those already on medication and feeling fine, there is no need to change their present regimen even if their blood pressures are lower than the newer goals

On the heels of the recent changes in cholesterol guidelines, it is fair to question the whole process of how these sweeping recommendations get made and where the process is taking us.

Both the cholesterol guidelines group and the hypertension guidelines group were appointed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the NIH. That is where the similarities tend to end. For example:

The cholesterol group tried to take a holistic approach to help decide who would benefit from statins by coming up with a formula that took into account other risk factors, such as the presence of diabetes, hypertension, smoking history, age, sex, and ethnicity. The hypertension group only took into account age. As patients with high cholesterol often have hypertension, it is difficult to reconcile these different approaches.

The cholesterol group looked for answers by reviewing different kind of studies, sometimes using studies of the “meta-analysis” – and “observational” type. The hypertension group instead looked almost exclusively at types of studies known as “randomized controlled trials”. Randomized controlled studies on large groups of people are very expensive to do so there are not that many out there to review.

In the absence of studies to prove something true, the cholesterol group was more likely to use a consensus of experts to come up with recommendations; while for the hypertension group, the absence of hard proof often meant no recommendation or even retraction of a previous recommendation. The case of blood pressure targets in diabetics is an example: For years primary care physicians, diabetic specialists, cardiologists, eye specialists, and kidney doctors have been advocating making the blood pressure goal for diabetics lower than for the average person in the hope that this would forestall some of the feared complications of the diabetes. However, the hypertension group felt there were no definitive studies out there to answer the question as to whether that really was true and therefore deemed the lower blood pressure goal no longer valid. According to this type of thinking, no definitive data one way or the other carries the same weight as adverse data.

Depending on one’s personal experience and training, different doctors may agree or disagree with some of these newer guidelines. I for one have always advocated less strict guidelines for elderly patients in the treatment of hypertension because of concerns about falls caused by over treatment, but conversely feel that most diabetics should strive for a lower blood pressure goal than the average person.

To be sure coming up with recommendations can be difficult. Definitive answers are not easy to come by particularly when a treatment may take decades to show an effect, as is the case with arteriosclerosis. Think of the new house you bought thirty years ago; now a pipe develops a leak. Was the leak due to the fact that the pipe was a then new plastic, or that ten years ago you switched from well to city water, or maybe it was that water heater that had a recall? Can’t figure out the reason for the leak? How about looking at the leak experiences of ten thousand homeowners combined? Still can’t find the answer? How about looking at the collective experience of a million homeowners? Aha! You think you’ve found the cause – but did you? Because now those million homeowners are spread out over different states with varying temperatures and humidity. Well, you get the picture.

Yet, when you see how different groups of smart people can come up with such seemingly divergent approaches to analyzing the literature and making recommendations, you can’t help but wonder if what we are seeing here has as much to do with who is invited to be on these groups and the personalities of group members and their leaders. For those of you who have served on committees given expansive charges and latitude, this should be no surprise.

These “recommendations” are becoming increasingly important for a number of reasons. First, for those interested in promoting quality they provide a quick and easy way to judge the “quality of care”. So, if all your patients are meeting the new guidelines then your care is considered good – Never mind that last year when the guideline recommendations were different your care was considered less than optimal. Insurance companies such as United Health (profits of 7.2 billion dollars last year) want to prove to their large group customers that there is value to the high premiums they charge and that they are doing something to help keep their employees healthy. As a result tracking adherence to recommendations has itself become a big business as insurance companies contract with companies to scan medical records and review prescription records and then send faxes to doctor’s offices suggesting changes in medications. What we really need is a study to see if any of this accomplishes anything other than killing a lot of trees and diverting doctors and their staff from doing what they are supposed to do – which is to take care of you.

Similarly, in the name of “quality” insurance companies may not want to pay for medications for individuals who are outside the “recommendations” unless the doctor’s office goes through a complicated prior authorization process. Finally, these one size fit all recommendations fit well into a growing pattern whereby experienced physicians are being judged by computerized checklists and increasingly replaced by non physicians such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants who, given their more limited experience and training, are more likely to use computer generated guidelines when providing care and less likely to step outside the box.

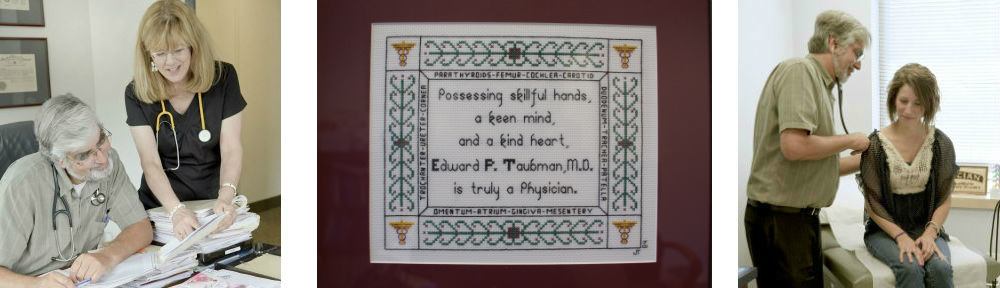

There was a time when patients came to their physician with the hope that their doctor’s experience would help them come up with a recommendation personalized to them. In the medical field we call that “clinical judgment”. And the sign of a doctor with good clinical judgment was that, when they didn’t know the answer, they would ask a colleague whom they trusted to share their expertise. Medical reports then tended to read, “In my experience Mary would benefit by….” Nowadays the computerized reports tend to read, “According to the Jupiter trial Mary would benefit by…” For better or worse – the new recommendations, and in particular those of the hypertension group, seem to be taking us further away from that lofty goal of personalized medicine.

p.s. Like what you are reading? Please share with your friends and neighbors using the links below! Want to start a new topic or start receiving weekly e-mail summaries of our health blog?? Click Here